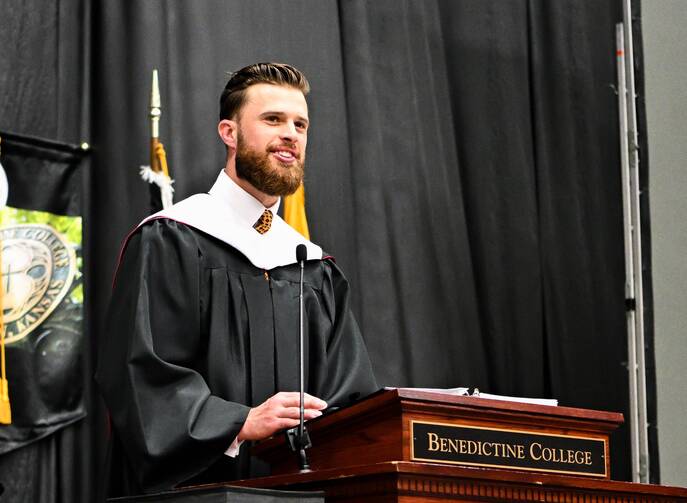

Many people have called on Benedictine College to apologize for the commencement address by Harrison Butker, the placekicker for the Super Bowl champion Kansas City Chiefs, in which he described “timeless Catholic values” in a manner that many found sexist and homophobic. I’m not sure about that, but I do think the college should apologize to Mr. Butker.

I say this as an editor, whose work is in one important way the same as the work of those who choose commencement speakers. As I understand editing, you must try to keep your writers from looking bad, even in cases where they may not realize for some time how bad they look. You should be as solicitous for their reputation as you are for your own.

Some may argue that no one is responsible for keeping adults from embarrassing themselves. That seems to me, especially as someone who is also a writer, as a failure of “do unto others” ethics. You act not only for your writers but also for your readers. Anything foolish, uncharitable or unbalanced from your writer can mislead some readers and keep others from hearing the good things the writer has to say.

Those who choose graduation speakers have the same responsibilities. Benedictine College should apologize to Mr. Butker for putting him in a position he should not have been in—and which he was not wise or mature enough to avoid.

Older and wiser people could have helped him, as good editors help their writers, to say what he felt he needed to say and avoid saying anything else. Someone could have told him, for example, that the line “Congress just passed a bill where stating something as basic as the biblical teaching of who killed Jesus could land you in jail” would be heard as an antisemitic dog whistle and explained that natural family planning should not be described as “Catholic birth control,” and in various ways helped him write an address that would be more forceful because it was more thoughtful.

This may be an “old guy” point, but I was him once, and I think I know how Mr. Butker thought about the address because I once thought about my writing that way: as a chance to say what needed to be said, to speak the truth and the hard word, to challenge the culture and defy the establishment, to encourage discouraged people, to strike a blow for God and his church.

Absent (at least in my case and I am fairly sure in his) was any recognition of how much I didn’t know and how complicated some matters are, and how easily I could say something that was striking but only superficially true. Absent also was any realization that rousing listeners does not necessarily help them and that immediate praise (which I always expected) would not mean I had said anything useful.

I was clever and verbally adept and wrote things that readers of some small Protestant magazines liked. No one, as far as I remember (and I admit I could have missed this entirely), told me I didn’t know enough, that I should narrow my subjects to the relatively few I could write on with some authority. No one warned me that intelligence and gifts weren’t enough, and explained what wisdom required. I would have grown faster as a writer had they done so.

In my editorial work, I have tried to help many people tell their stories and, in so doing, bring others into their experience in a way that might move their thoughts and feelings. A good part of that work is keeping many of them from making ideological or political claims that are either untrue or unjustified by what they have written.

But that is what many people seem to think public discourse is: combat, not communication. They want to rally the troops and charge into battle against the enemy. They measure their success by the cheers from their side and the anger of the other, not by helping others see something they didn’t see before.

That kind of speech doesn’t change anyone, doesn’t make them a little more open or less certain, more respectful of how other people see the world, more willing to learn from others and more inviting to others to learn from them. It tends to make them less so.

Mr. Butker could have given a good commencement address that might have said something useful to different people. He could have encouraged and challenged the kinds of American Catholics who like culture-warring addresses, and challenged and encouraged those who don’t. He could at least have made the latter see how his life made sense to people like him as an expression of Catholicism’s good news.

But he didn’t. He gave the kind of talk he was capable of giving, on an occasion that required more wisdom and maturity than he has—and more than he should have been expected to have.

What commended Harrison Butker as a commencement speaker, besides the accidental combination of his minor fame as a football player and his traditionalist Catholicism? Why did the college ask him, except to enjoy the benefits of his celebrity? They put him in a position he should not have been put in. For that, they should apologize to him.

I am sure he doesn’t care now. I certainly wouldn’t have, had I had his success. But he may care, he should care, when he’s older and has learned more about life and the world, and thinks about how much good he could have done if someone had helped him speak more wisely.

_0c1ad.jpg)